Reverse-Engineering a Boat Propeller from 3D Scan Data

Client: Private marine repair business

Services: 3D scanning, mesh processing, reverse-engineering exploration

Timeframe: ~6 months (on and off)

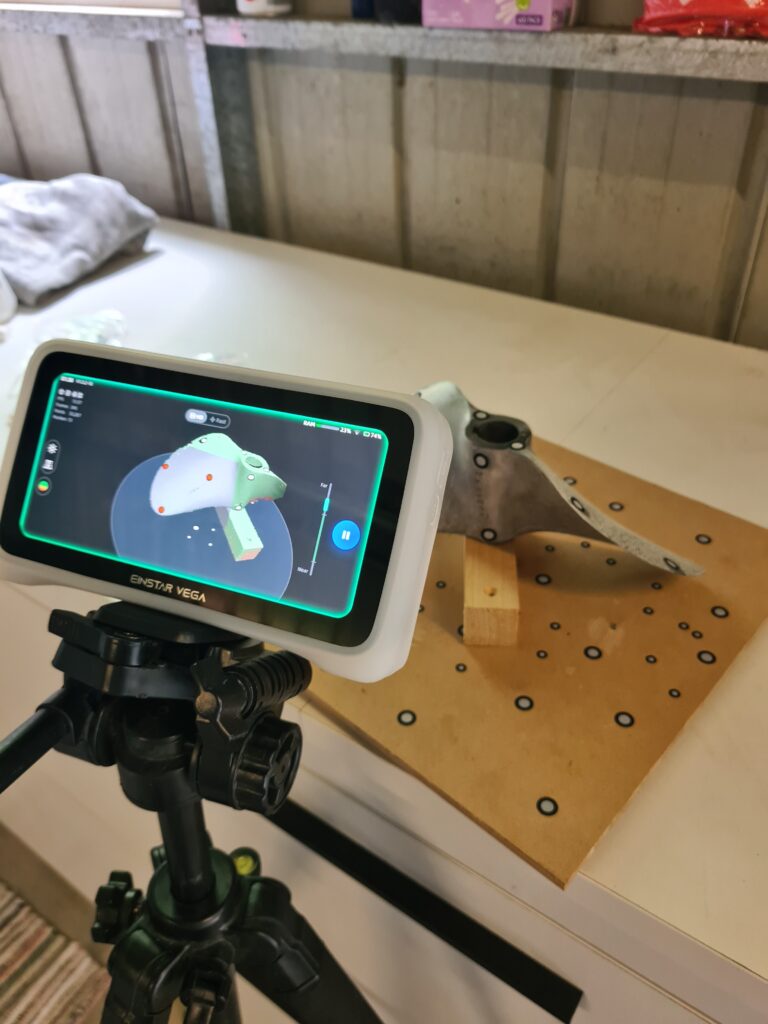

Tools: Einstar Vega → blue-laser scanner, Fusion 360, Geomagic

Project Background

A marine client approached me to digitise a set of six small boat propellers.

The original plan was simple: 3D scan each prop, 3D print patterns, and use those to create moulds for casting new propellers.

I had just purchased my first 3D scanner and saw this as the perfect opportunity to test it on a real-world job.

Scanning Challenges

I started with an Einstar Vega scanner and a turntable covered in tracking targets. The setup looked solid, but I quickly ran into limitations:

- The scanner struggled with thin, sharp edges – exactly what a propeller blade has.

- As I moved around each blade, tracking drift caused the two sides of the blade to misalign. Blade tips overlapped or floated instead of meeting cleanly.

What I expected to be a one-hour scan turned into several hours of rescans and alignment fixes.

During processing, the software failed to properly fill the recesses where the tracking stickers had been. Instead, it left small voids and craters in the mesh.

For direct 3D printing, that level of damage is unacceptable.

I delivered the best meshes I could at the time, but it was clear that “scan → print” wasn’t going to be a clean path for this project

Pivot: from “scan & print” to reverse-engineering

Rather than forcing poor-quality meshes into production, I suggested a different approach:

use the scans as reference data and rebuild the propeller as a clean, parametric CAD model.

To do that properly, I needed to understand the underlying blade geometry, not just its outer surface.

Understanding the blade as an airfoil

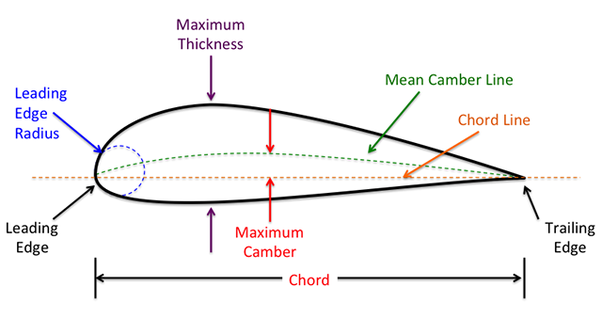

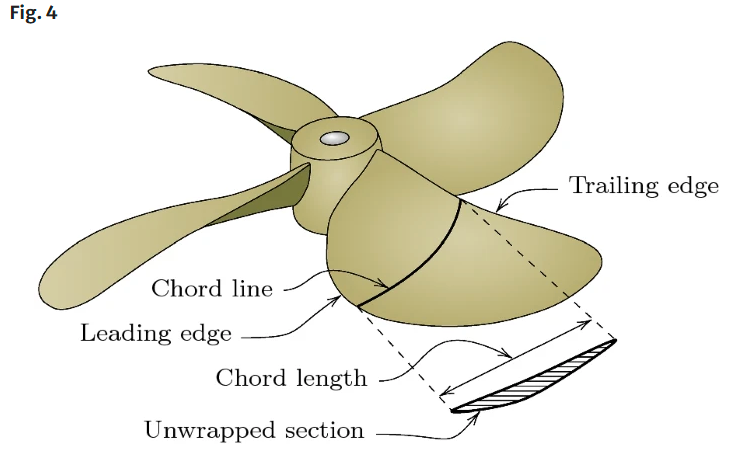

I studied propeller and airfoil theory and learned to describe each blade section using:

Leading and trailing edges

Chord line and chord length

Camber and maximum thickness

Local twist at a given radius

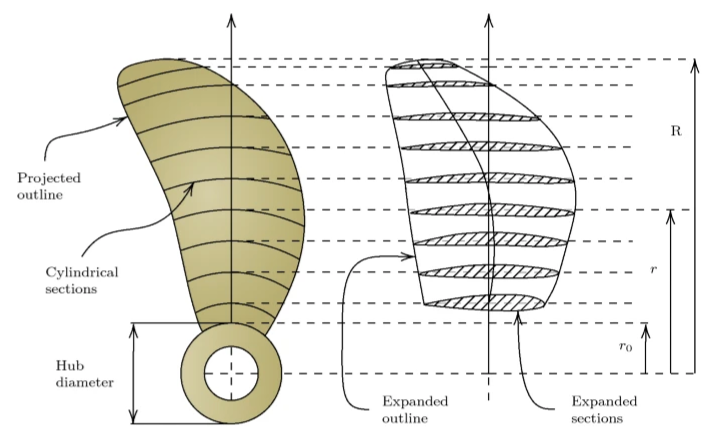

I realised that a propeller is essentially a series of twisted airfoils stacked along the radius of the blade.

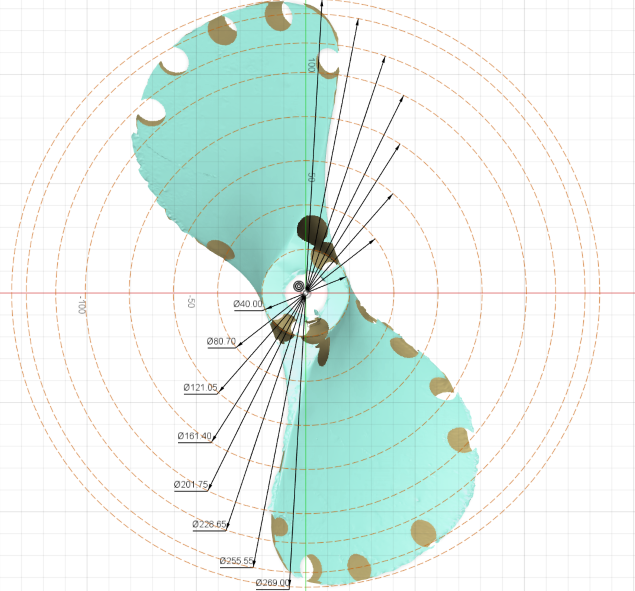

Sectioning and parameter extraction

Traditional documentation often uses cylindrical sections at different radii. These are useful, but they don’t fully describe the real 3D curvature of the blade.

What I really needed were unwrapped radial sections that exposed the true airfoil shape at each radius, including:

Accurate chord length

Leading-edge position

Thickness and camber distribution

Local twist angle

Using Fusion 360 and the scan as reference, I experimented with creating these sections and measuring the key parameters.

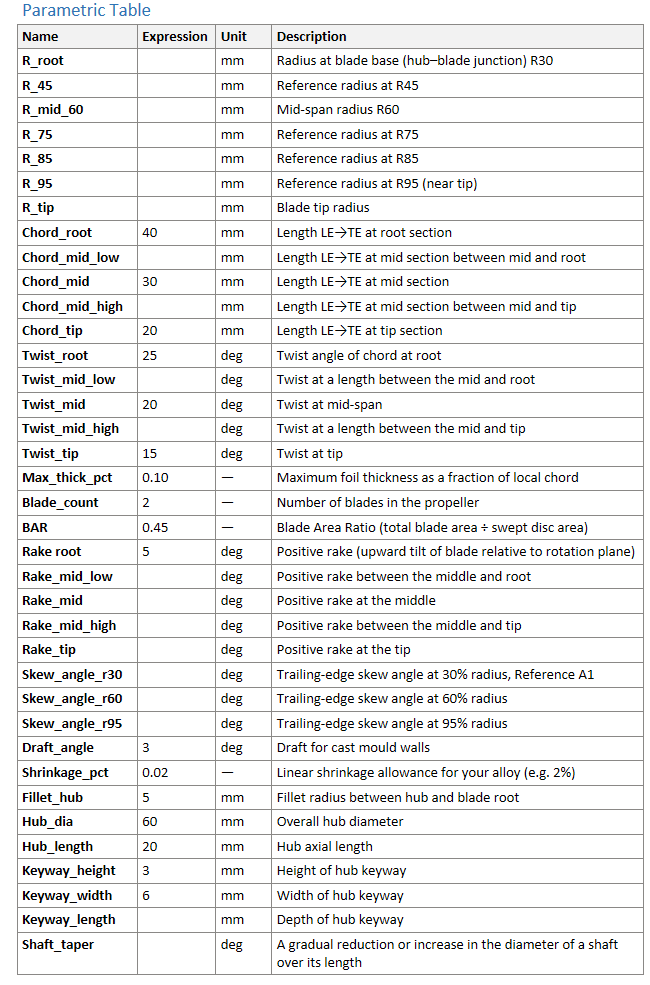

To organise the data, I built a parametric table that captured:

Radii from hub root to tip

Chord length at each station

Twist angles at each station

Maximum thickness as a percentage of chord

Rake and skew angles

Hub diameter, keyway size, draft and other casting-related features

My goal was to eventually drive a fully parametric propeller model from this table and loft between the defined sections.

Hitting the limits (and acknowledging them)

At that time, I ran into two main constraints:

Software fit: Fusion 360 is powerful, but it isn’t optimised for detailed propeller reconstruction.

My experience: I didn’t yet have the modelling depth to build the robust parametric blade I had in mind.

Rather than forcing an unreliable model, I paused the reverse-engineering effort and focused on delivering what I could: the best scans available at the time, and a clear explanation to the client of where the limitations were.

Level-up: new scanner, new workflow

A few months later, I invested in a blue-laser scanner that handles sharp edges and shiny metal far more accurately. With it, I was able to capture new propellers for the same client with:

Clean blade tips

Stable tracking

High-resolution, watertight meshes

I also moved into Geomagic for reverse-engineering. It’s designed specifically for turning scan data into CAD and offers much better tools for complex organic geometry like propellers. The trade-off is a much steeper learning curve, which I’m actively working through.

The client’s goals have evolved with this upgrade: he’s now interested in production-ready CAD models that can be taken straight to CNC machining or specialist manufacturers.

Current status

The client has high-quality 3D scans of his propellers that can already be used or shared with other designers.

We’re exploring a path to fully parametric CAD models, balancing software costs, specialist input, and the level of accuracy required.

I’m developing a repeatable scan-to-CAD workflow for propellers that I plan to offer as a dedicated service in the future.

What I learned from this project

Be transparent about capabilities. Saying “yes” is easy; delivering on it is harder. Clear communication around risk and uncertainty keeps client relationships healthy.

High-end tools don’t replace skill. A good scanner and CAD package are only half the story—the rest is practice, experimentation, and understanding the underlying physics.

Understanding the theory pays off. Learning about airfoils, chord, camber, twist, rake and skew has changed how I think about any rotating blade, not just propellers.

Iterative improvement is okay. This project didn’t follow a straight line from brief to final part, but it has significantly lifted my capabilities in 3D scanning and reverse-engineering.