Automotive HVAC Controller

Summary

This long-running personal project tracks the evolution of a complete redesign of the HVAC control system in a 1991 Nissan Silvia S13.

What began as “get the air-con working again” turned into a multi-year exploration of:

Embedded control (Arduino → ESP32 planned)

Actuator selection and feedback (DC motors vs servos)

EMI-aware wiring in a noisy automotive environment

Moving from ad-hoc prototyping toward CAN-based, PCB-driven system design

It’s included here not because of the car itself, but because it documents how the approach to engineering has matured over 8–10 years.

Context

The Silvia’s factory climate control system had several problems:

Damaged and hacked cabin wiring to the original HVAC control unit

Ageing 12 V vent motors with weak torque and worn positional feedback tracks

No reliable fan or air-conditioning control in a black car used in a hot Australian climate

The goal for this project was to replace that fragile, ageing system with:

A modern and maintainable electronic control system

A more intuitive and contemporary user interface

A design robust enough to live behind the dash alongside a PDM-based ECU and other noisy electronics

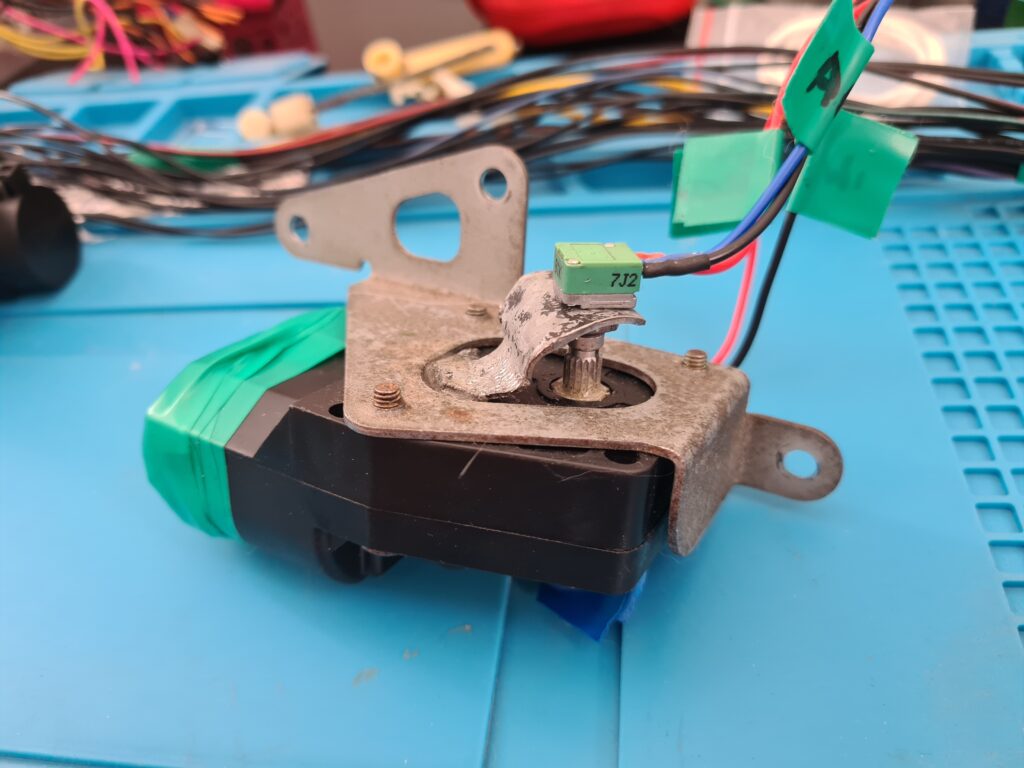

Original Hardware Assessment

The original vent motors and feedback mechanisms were disassembled and inspected. Replacement DC motors were sourced, but the brittle resistive pads used for position sensing were not suitable for a long-term solution. At this point the direction shifted from repairing OEM hardware to designing a replacement system.

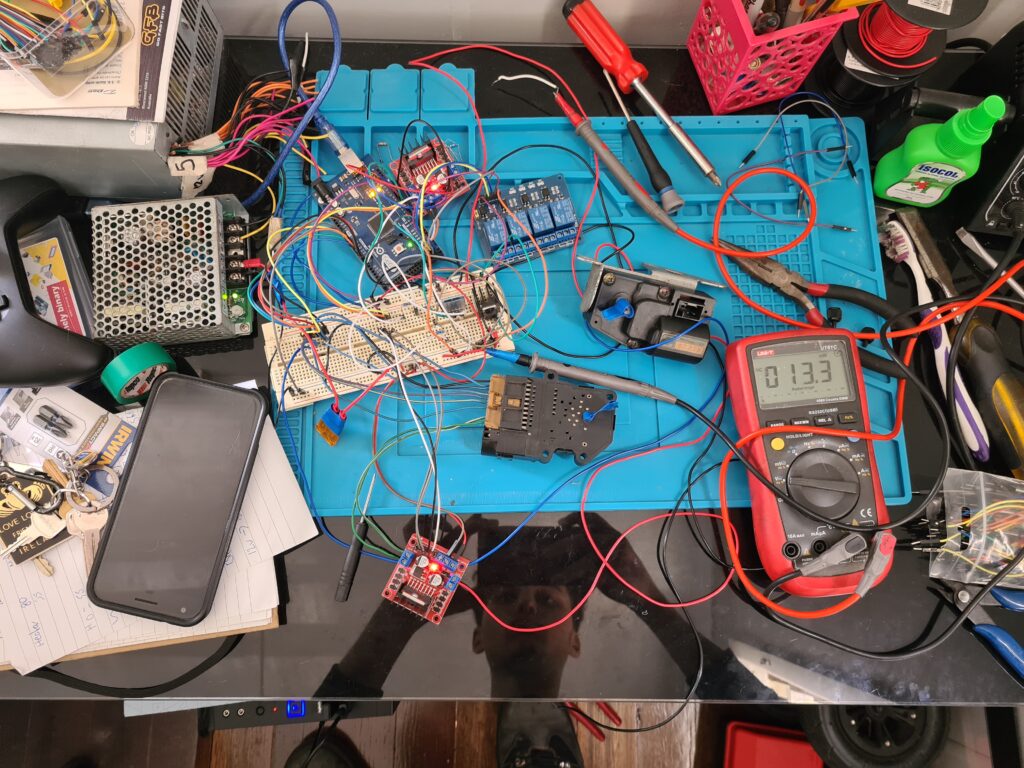

Mk1 – Arduino Control, Hacked Motors and Bluetooth UI

Mk1 was developed while still working as a cabinetmaker, before beginning formal engineering studies. The core idea was:

Reuse the factory vent mechanisms

Add external potentiometers for position feedback

Use an Arduino and H-bridge drivers to implement closed-loop control

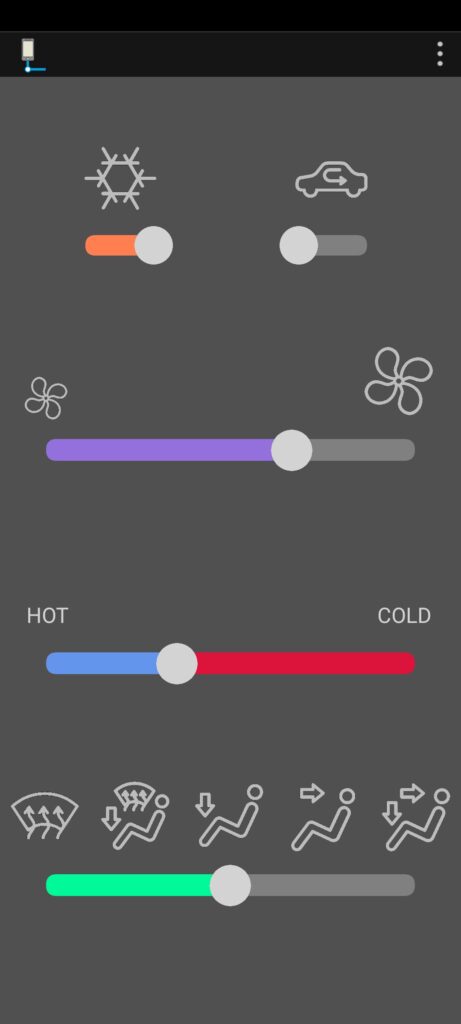

Control the system from a phone via a Bluetooth-based UI

Key features of Mk1:

Closed-loop vent position control using external potentiometers

Relay control of the original blower resistor pack and compressor clutch

A custom phone UI for fan, mode and temperature commands

An isolated power supply module to help protect sensitive analog feedback from automotive noise

Mk1 met its functional goals on the bench but revealed important limitations:

The hot-glued potentiometer couplings to the motor shafts were mechanically fragile.

The wiring strategy relied heavily on analog signals and isolated supplies that would have been hard to trust long-term, buried behind the dashboard.

Mk1 was intentionally retired at the prototype stage, once it had delivered its main value as a learning platform.

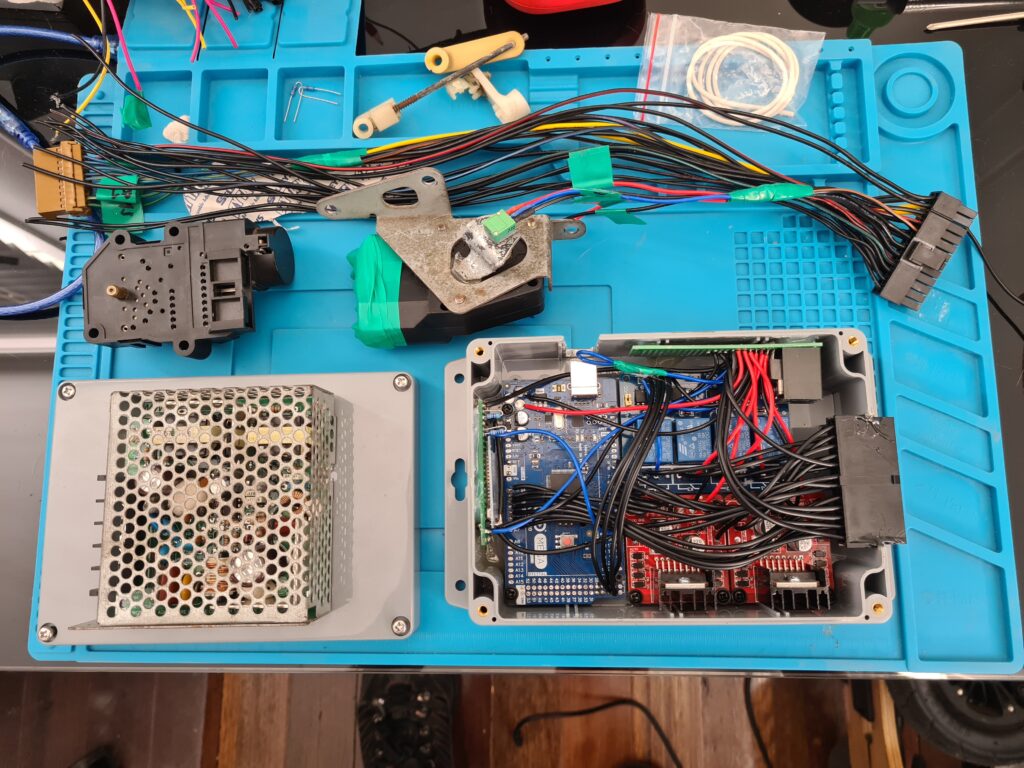

Mk2 – Servos, Shielded Wiring and a Modern Control Panel

After focusing on other major work on the car (engine rebuilds, wiring cleanup), the HVAC project was revisited with more experience and a clearer approach.

Key changes in Mk2:

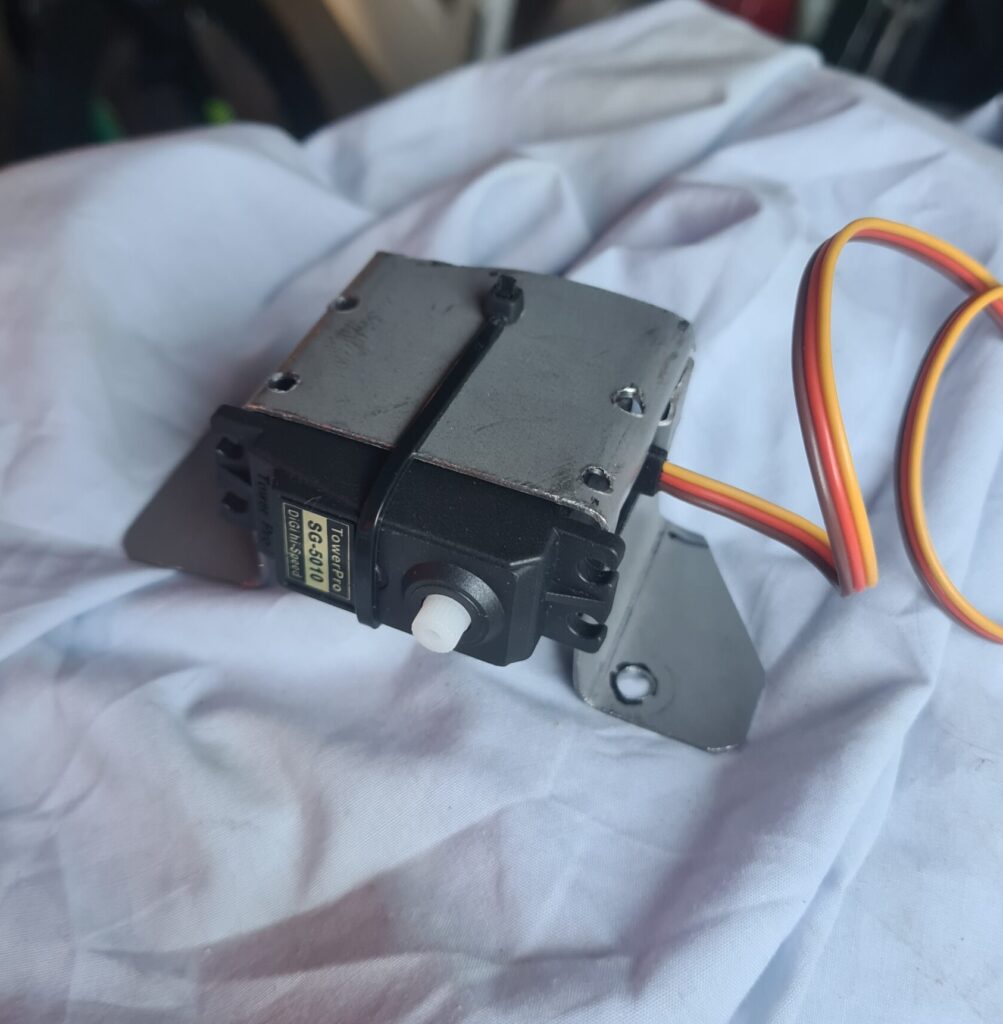

Actuators:

Factory vent motors were replaced with hobby servos.

Custom brackets were hand-fabricated to mount servos in the original locations and drive the existing blend doors.

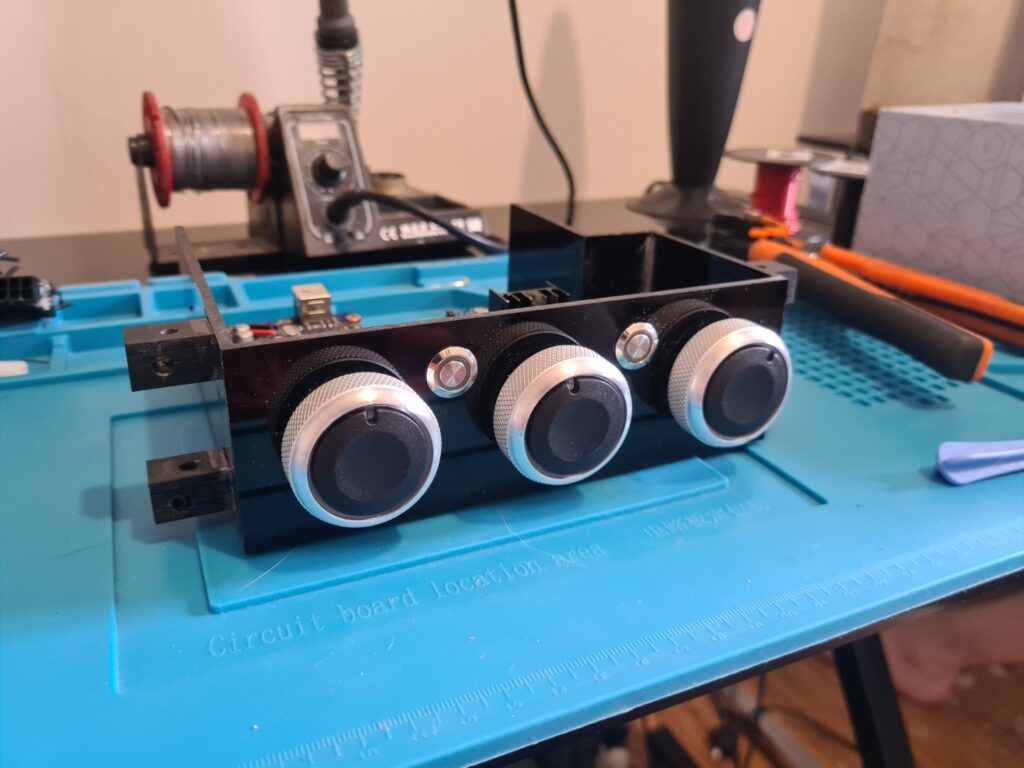

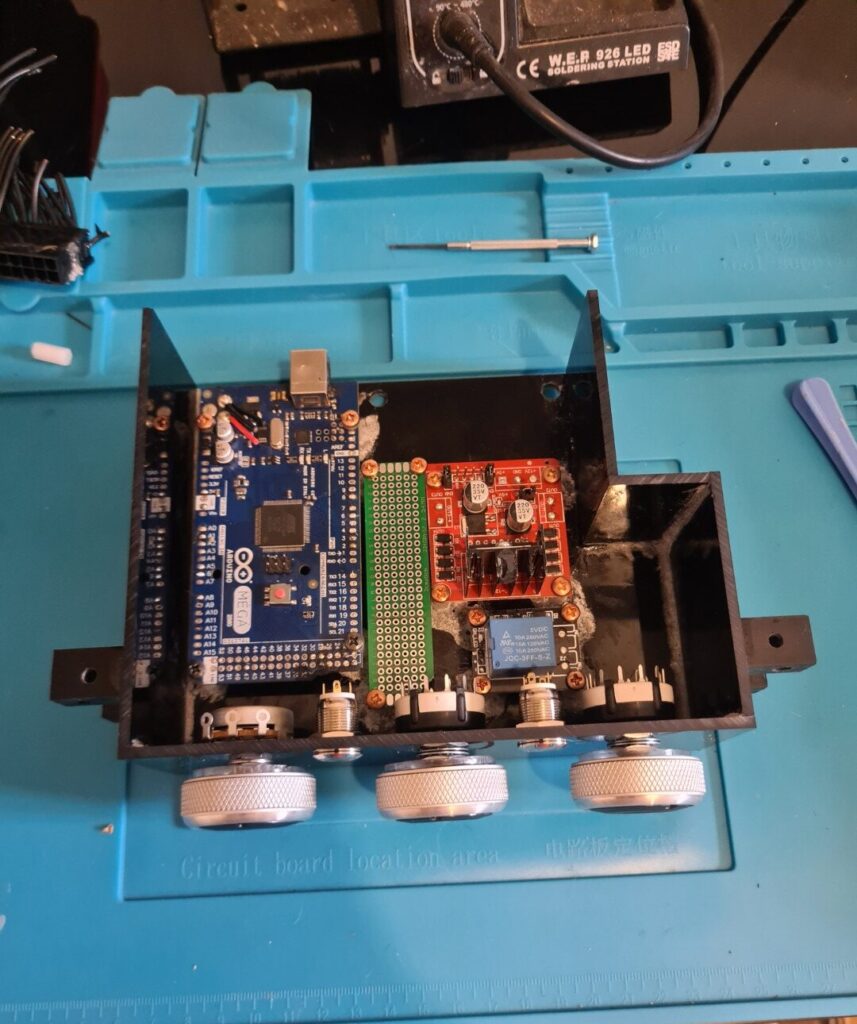

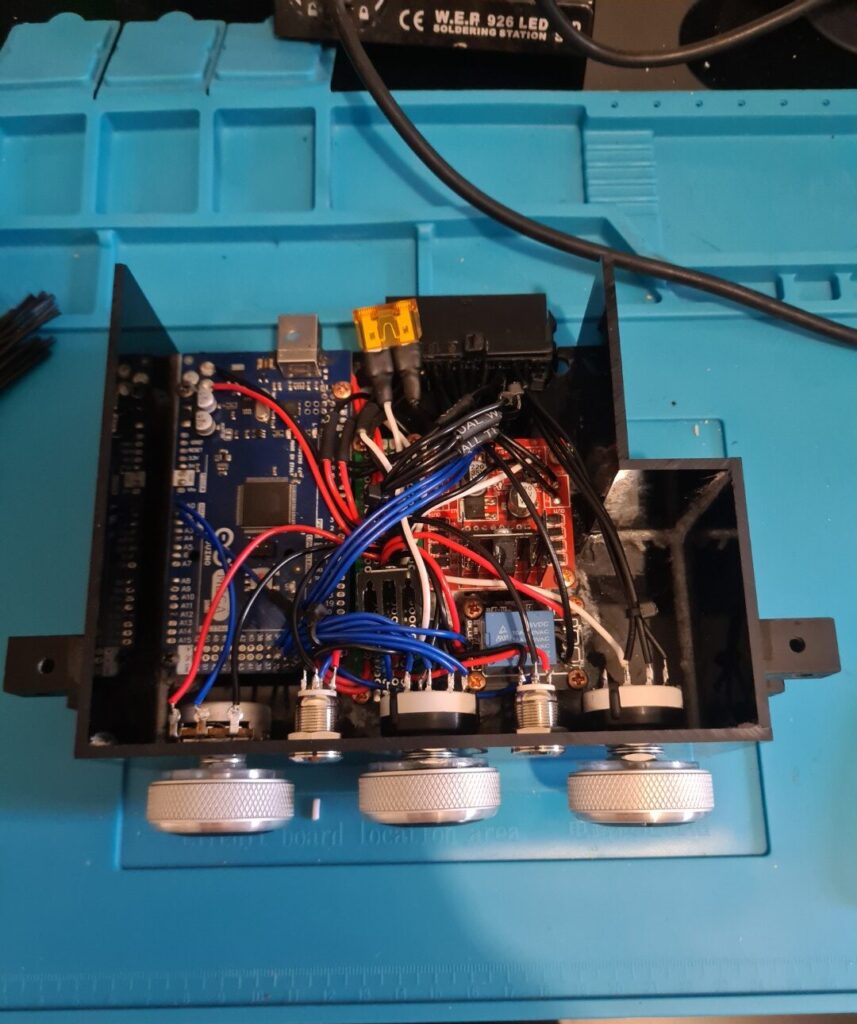

Electronics & interface:

The system was consolidated into a single compact enclosure.

An Arduino Mega controlled two servos via a motor driver and switched the compressor via a relay.

A new front panel was created with:

Left knob: temperature (potentiometer, cold → hot)

Middle knob: vent mode (rotary switch: face, face/feet, demist, etc.)

Right knob: fan speed (rotary switch: off, low, medium, high)

Illuminated push buttons for A/C and recirculation

EMI-conscious wiring:

From other projects (e.g. sim racing hardware), it was clear that EMI management would be critical.

Industrial-grade shielded cable was selected: twisted pairs with full metal braid and a heavy outer sheath.

The intention was to run all sensitive signals (servo control and feedback) through these shielded looms to protect them from the noisy environment behind the dash.

Mk2 represented a significant step up in terms of mechanical packaging, user experience and EMI awareness.

Why Mk2 Stopped at Prototype

Despite Mk2’s progress, there were clear reasons not to install it:

Blower motor control not fully solved

The factory blower motor draws approximately 40 A on startup.

At that time, there was no high-current PWM solution in place that was robust enough for long-term use.

Continuing to lean on the original resistor pack and simple relays didn’t align with the direction of the build.

EMI and future system context

Even with high-quality shielded cable, Mk2 still relied on relatively long analog signal runs for servo control and feedback.

The space behind the dash will also house a PDM-based ECU, switching:

Injectors

Relay coils

Fans, pumps and other loads via PWM

This makes the region behind the dash an increasingly harsh EMI environment.

Installing an analog-heavy system there would likely result in difficult-to-trace interference issues later.

Timing and priorities

Around the same time, personal priorities shifted (marriage, moving house, the start of a Mechatronics degree).

Given the outstanding technical concerns, fully installing Mk2 was not the best investment of time.

Mk2 therefore remains as a fully functional, bench-tested prototype that demonstrates a more mature approach, but it is intentionally not the final implementation.

Mk3 – Planned Architecture

Mk3 is a clean-sheet redesign inspired by the lessons from Mk1, Mk2 and current studies in Mechatronics Engineering.

Planned characteristics:

Custom PCB

Integrate servo control, blower control, compressor safety logic and IO onto a dedicated PCB rather than stacking modules.

CAN-centric architecture

Use CAN bus, in line with the rest of the car’s PDM-based electronics:

Differential signalling to improve EMI robustness

Shorter analog runs and smarter nodes placed close to actuators and controls

Cleaner integration with other CAN devices in the vehicle

Modern microcontroller platform

Move from Arduino Mega to an ESP32-class MCU.

Firmware likely implemented in C/C++, with the option of exploring Rust for increased safety.

High-frequency blower PWM

Design a driver stage for the blower to operate above audible range (≈25 kHz), balancing:

Reduced acoustic noise

Smooth speed control

Robust handling of inrush currents and thermal load

Refined user interface

Retain the tactile strengths of Mk2 (knobs, clear physical controls).

Consider modern elements such as encoder-based knobs with integrated displays or small OLEDs, depending on how the broader interior design evolves.

Skills and Takeaways

This project demonstrates:

System-level thinking

Viewing “HVAC control” not as a single circuit but as an integrated system of UI, actuators, power electronics, sensing, communication and environment.Iterative engineering and decision-making

Using Mk1 and Mk2 as learning stages, then deliberately choosing not to deploy them when they no longer met reliability or architectural requirements.Designing for real-world constraints

Considering heat, vibration, EMI, serviceability and future upgrades (e.g. PDM-based ECU and CAN expansion) from early in the design.Transferable technical skills

Embedded control and firmware development

Mechatronic integration (mechanical + electrical + software)

EMI-aware wiring and system layout

Human-centred control design (physical interface and UX)

This HVAC project is one component of a much broader, ongoing re-engineering of the vehicle’s electronics. It serves as a good snapshot of how the approach to engineering problems has evolved—from hot glue and perfboard toward structured, communication-aware, PCB-based system design.