DIY Direct-Drive Simulator Wheelbase

A from-scratch, high-torque direct-drive steering wheelbase for drifting simulation, built around a repurposed BLDC hub motor, open-source motor control hardware, and several generations of custom encoder and mounting solutions.

Summary

I set out to replace an aging gear-driven Logitech wheel with a home-built direct-drive system that could deliver much higher fidelity and torque, without the cost of a commercial unit. The project became a deep dive into BLDC motor control, encoder technologies, power electronics, and practical mechanical design using 3D printing.

- High-torque BLDC hub motor driven by an ODrive development board and OpenFFB CAN interface

Custom 3D-printed and steel-reinforced motor mounting to a timber sim rig

Multiple encoder architectures: belt-driven rotary encoder → magnetic ring → on-axis Hall sensor in the motor shaft

Custom brake resistor and power stage to handle regenerative loads

Real-world experience with EMI, shielding, and the limits of rapid prototyping

Context

I originally ran my drifting simulator on a simple wooden frame with a car seat and a Logitech gear-driven wheel. It was great for getting started, but as I got more serious about competitive drifting online, its limitations became hard to ignore:

The plastic geartrain had noticeable backlash and compliance.

Fine details in tyre grip and vehicle balance were muted or lost.

Peak torque and dynamic range were limited.

Commercial direct-drive wheelbases solve these issues by coupling a powerful motor directly to the steering shaft, but they’re expensive. At the time, I couldn’t justify the cost, and I had just enough tools and curiosity to consider building my own:

A small but well-tuned 3D printer

Growing confidence with CAD

Willingness to work with development boards and open-source firmware

The goal was to build a usable, high-fidelity direct-drive wheelbase as cheaply as possible using a second-hand hub motor, off-the-shelf electronics, and a lot of iteration.

Design & Iterations

Foundation: Motor, Mounting, and Control Stack

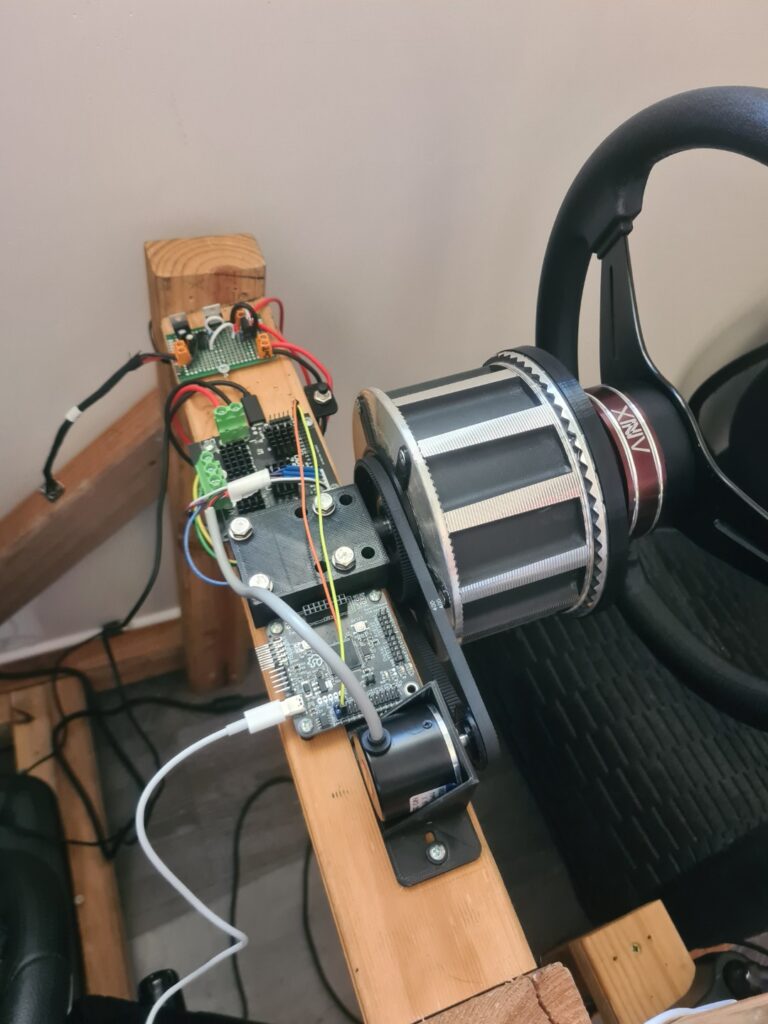

I chose a second-hand BLDC hub motor—the same style used in hoverboards and small electric toys. It’s compact, torquey, and designed to spin a “wheel” by construction.

I measured the housing with digital calipers and designed a clamp-style 3D-printed mount that wrapped around the motor and bolted it to my existing timber rig. This formed the mechanical backbone of the project.

On the control side:

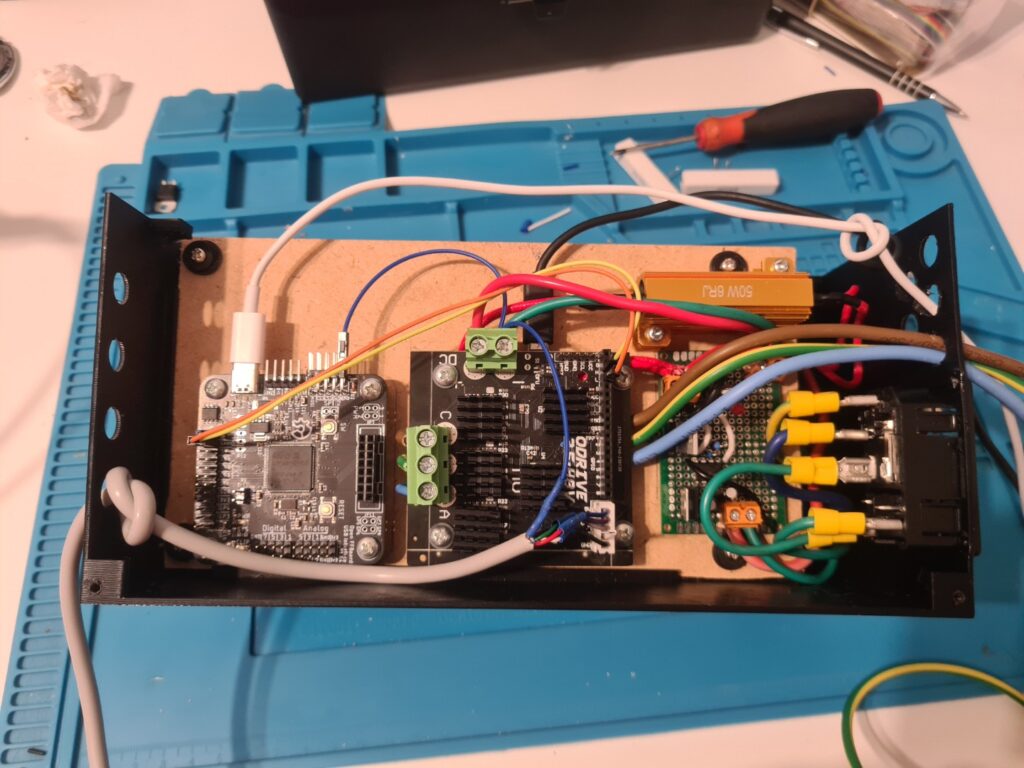

Motor drive: ODrive development board (three-phase BLDC control with encoder input)

PC interface: OpenFFB board communicating with the ODrive over CAN, translating force-feedback commands into torque targets

For power, I initially used a high-wattage gaming laptop power brick that matched the required DC bus voltage.

To handle regenerative braking and protect the PSU, I hand-built a perf-board circuit:

MOSFET-controlled brake resistor

Voltage thresholds configured in firmware to dump excess energy into the resistor when the bus voltage rose during aggressive steering events

This worked until misconfigured limits allowed a large regenerative event to over-voltage the laptop PSU and destroy it. I replaced it with a proper industrial DC switching power supply from AliExpress, with more comfortable headroom in both current and voltage.

As torque levels increased, the original 3D-printed motor clamp began to deform—under both rotational load and side loads from the driver pulling on the wheel. I reinforced the mount with a steel plate pressed against the motor’s flat and bolted through the frame, preventing the motor from twisting and slotting the plastic over time.

From here, the main challenge became precise, reliable position sensing for the motor.

Version 1: Belt-Driven Rotary Encoder

The first encoder solution used a dual-channel incremental rotary encoder designed for industrial machinery. Because the hub motor didn’t expose a convenient encoder shaft, I:

3D-printed a bracket that bolted to the back of the motor

Added a GT2 timing belt between a pulley on the motor shaft and a pulley on the encoder

Configured the pulley tooth counts in the ODrive so it could convert encoder counts to absolute motor angle

This gave me flexibility in gear ratio and allowed the encoder to spin at a manageable speed.

However, two critical issues emerged:

At high steering speeds, the encoder pulse rate could exceed what the system reliably handled, causing occasional loss of position and forcing recalibration.

The 3D-printed bracket and motor mount flexed under torque, upsetting belt alignment and sometimes causing teeth to skip under load.

This version proved the concept but demanded constant mechanical tuning and didn’t reach the level of reliability I wanted.

Version 2: Linear Rail Tensioner & Stiffer Mounting

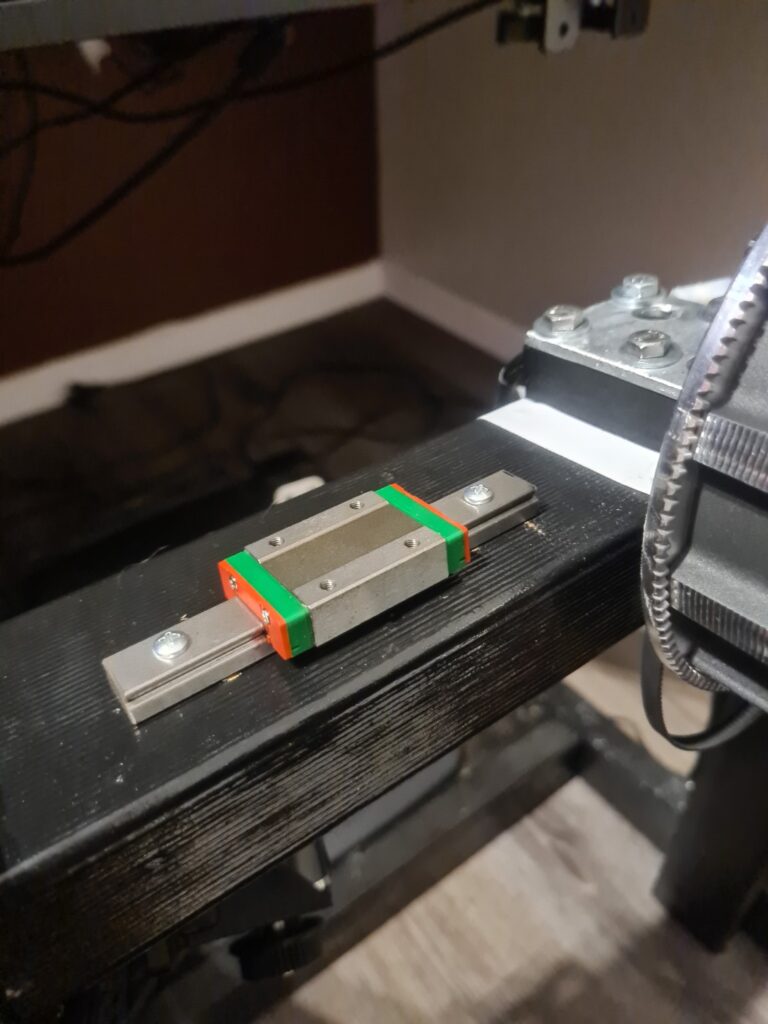

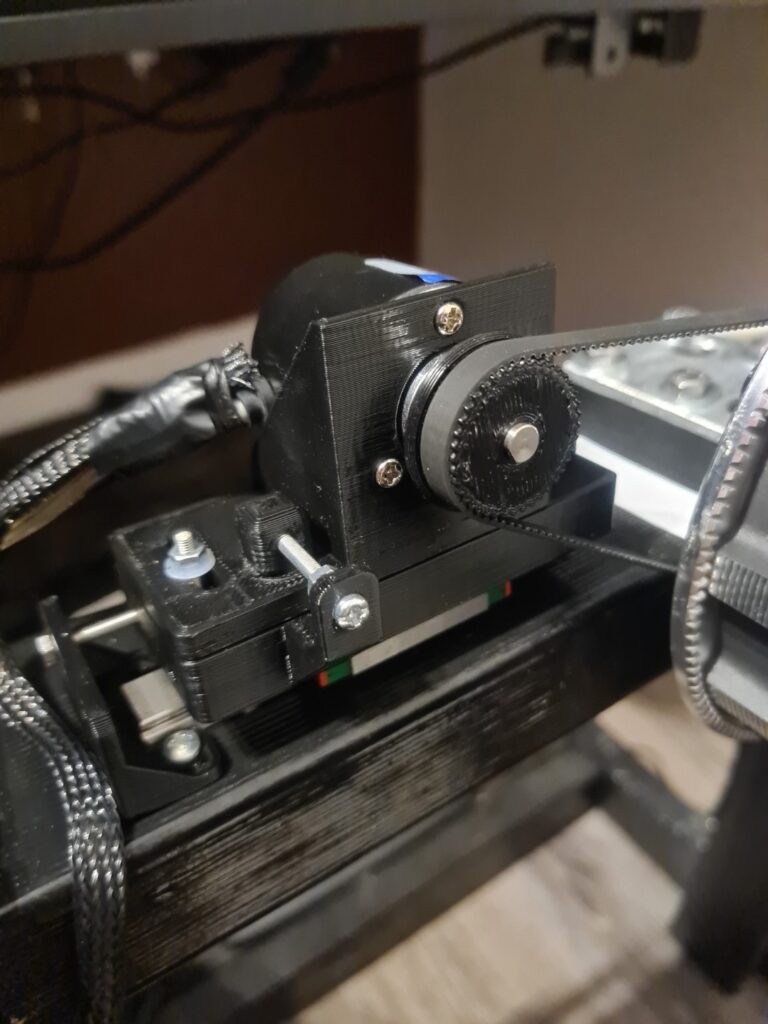

To address the belt alignment and tension issues, I reused a spare MGN-style linear rail from a 3D-printer project. I cut it down and designed a new encoder assembly around it:

The encoder sat on a 3D-printed carriage running on the linear rail.

Sliding the carriage adjusted belt tension along one axis.

Additional offset screws allowed fine control of angular alignment, preventing the belt from “walking” off the pulleys.

Once tuned, lock-down screws transferred the load away from the adjustment screw threads.

At the same time, the main motor mount was stiffened with a steel plate clamped onto the motor’s flat, eliminating the deformation that was previously visible when applying steering torque.

This combination significantly improved mechanical stability and belt behaviour, but it didn’t completely eliminate intermittent encoder issues—particularly under aggressive drifting inputs.

EMI and Signal Integrity

Running a low-level encoder signal next to a high-current, PWM-driven BLDC motor exposed a new class of problem: EMI.

The encoder cable was multi-core shielded, but initially the shield wasn’t terminated. This, combined with suboptimal cable routing, led to noise and jitter in the encoder signal.

I iterated on this by:

Replacing the cable with a higher-quality shielded cable

Properly grounding the shield at one end

Re-routing encoder and power cables to minimise coupling

Cleaning up grounding to reduce the chance of ground loops

These changes improved behaviour but didn’t fully solve the reliability issues. The belt-driven incremental encoder felt like it had reached the edge of what it could provide in this environment, so I moved on to magnetic encoder concepts.

Version 3: Custom Off-Axis Magnetic Ring (Wrong Geometry)

To eliminate belts and mechanical slip, I explored magnetic encoders.

I sourced a small Hall-based magnetic encoder module and designed:

A 3D-printed magnet ring with tiny alternating-polarity magnets pressed into it

A matching 3D-printed mount that fixed the encoder module to the stator

The idea was for the outer magnet ring to rotate with the motor shell, while the fixed sensor read the changing magnetic field.

The implementation was clean mechanically, but it didn’t work electrically. After re-reading the datasheet and reverse-engineering the board, I realised the encoder IC I was using was designed for on-axis sensing (one magnet at the end of a shaft), not the off-axis multi-pole ring I had created.

This version became a very instructive dead-end: the hardware was well executed, but it was fundamentally incompatible with the chip’s sensing geometry.

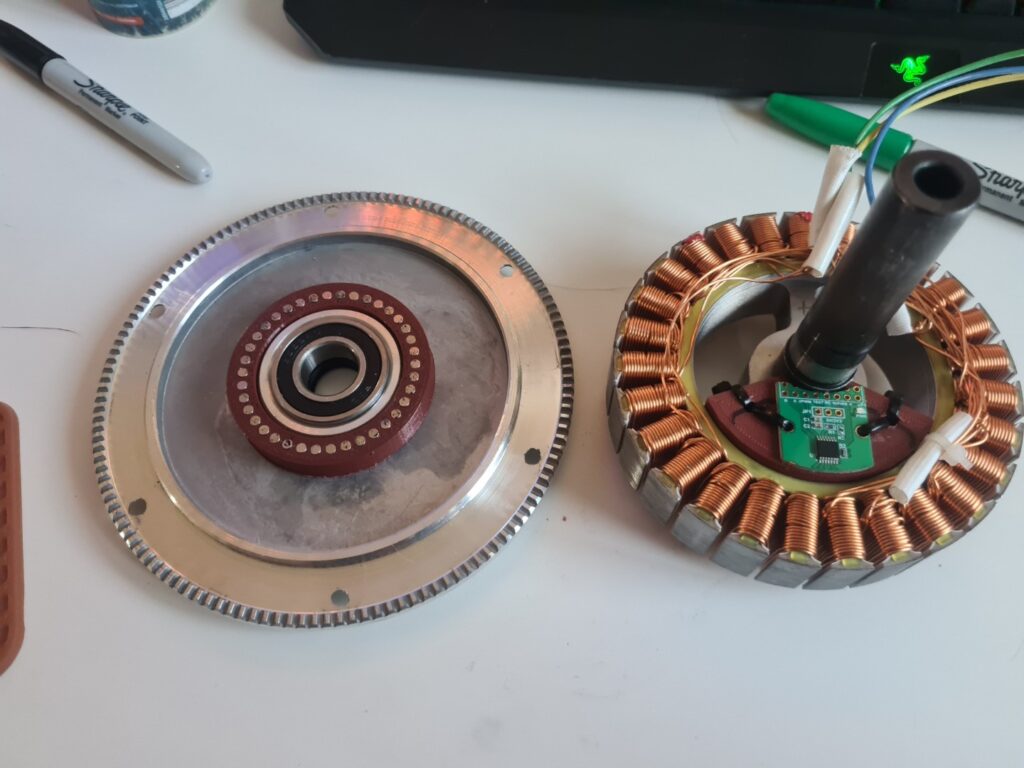

Version 4: On-Axis Hall Sensor Hidden in the Shaft

To make use of the on-axis encoder IC I already had, I rethought the geometry and moved the sensor into the centre of the motor:

- The hub motor’s stator shaft is hollow, with just enough space to host a small sensor.

I reverse-engineered the original module to identify the IC’s required connections (power, ground, output).

I hand-soldered fine wires directly to the chip legs, then potted the assembly in hot glue for mechanical strength.

I then:

- 3D-printed a plug that positioned the potted sensor at the very end of the hollow shaft

Installed a single magnet on the rotating hub, directly above the sensor, creating a true on-axis magnet + sensor pair

Routed a shielded cable through the assembly back to the control electronics

This was the cleanest and most elegant version mechanically: no belts, minimal moving parts, and a fully internal encoder. However, despite careful alignment, tuning, and firmware work, I couldn’t achieve the level of signal quality and robustness needed for a high-torque steering application.

At this point, the project had gone through several major redesigns and substantial troubleshooting. I had a deep understanding of the system, but I still didn’t have a wheelbase I could trust every day without tinkering.

Eventually, I made the pragmatic decision to retire the prototype and purchase a second-hand commercial direct-drive wheelbase to use for actual driving.

Final / Planned Architecture

Although the DIY wheelbase never reached “product-level” reliability, the final prototype architecture represented a coherent, system-level design:

Actuator

High-torque BLDC hub motor mounted via a steel-reinforced clamp to a rigid timber frame

Direct coupling to the steering wheel, no intermediate gearing

Drive & Control

ODrive development board for three-phase BLDC control and torque regulation

OpenFFB interface providing a CAN-based link between the PC and the motor controller for force-feedback commands

Power & Protection

Industrial DC switching power supply sized for sustained steering loads

Custom brake resistor and MOSFET switching circuit controlled by firmware thresholds to absorb regenerative energy safely

Sensing (Final Prototype)

On-axis Hall-effect encoder IC mounted in the hollow stator shaft

Single magnet on the rotating hub to provide angular position feedback

Shielded encoder cabling and considered grounding/cable routing to mitigate EMI

If I were to revisit this project with the same goals, the architecture above would form the foundation, with the main changes focused on:

- Specifying an encoder solution explicitly designed (and characterised) for this geometry and environment

Packaging and enclosure design for serviceability, safety, and cable management

Moving more elements from hand-built perf-board to robust PCBs

Skills & Takeaways

Technical skills demonstrated

3D CAD and mechanical design

Designing functional, load-bearing 3D-printed parts

Integrating steel reinforcement into plastic structures where needed

Using linear rails and adjustment mechanisms for precise mechanical alignment

Additive manufacturing for functional prototypes

Translating measurements into printed parts

Iterating on fits, clearances, and stiffness based on real-world testing

BLDC motor control & power electronics

Configuring an ODrive BLDC controller with external encoders

Designing and tuning a brake resistor circuit for regenerative loads

Understanding bus voltage limits, current draw, and PSU selection

Sensing, encoders, and EMI

Working with incremental rotary encoders, magnetic encoders, and Hall sensors

Recognising the importance of sensor geometry (on-axis vs off-axis)

Applying shielding, grounding, and cable-routing strategies to reduce noise

Embedded integration & open-source tooling

Using an open-source OpenFFB interface over CAN to bridge PC software and motor hardware

Debugging the interaction between firmware configuration, hardware constraints, and physical behaviour

Process & mindset

Iterative design under real constraints

Moving through multiple hardware revisions based on observed failure modes, not just theory

Balancing cost, complexity, and performance at each stage

Learning from failures

Turning dead-ends (e.g. the off-axis magnetic ring) into learning opportunities about data sheets, sensor selection, and system architecture

Recognising when a project has delivered its educational value, even if it doesn’t become the final tool in daily use

System-level thinking

Considering the full stack—from mechanical mounting and power delivery to sensing, control algorithms, EMI, and user experience

Keeping the end goal in sight: a reliable, high-fidelity steering feel, not just a technically “interesting” mechanism

For future clients and employers, this project is a good example of how I approach complex, cross-disciplinary problems: by breaking them into subsystems, iterating quickly, validating in the real world, and being honest about when to redesign, when to simplify, and when to buy instead of build.