Custom Load-Cell Brake Pedal for Sim Racing

I set out to design and prototype a realistic, force-based brake pedal for my sim racing setup, built around a load cell and 3D-printed structure, with geometry inspired by high-end commercial pedals.

Summary

This project started as an attempt to replace the basic position-sensing pedals from a Logitech G27 with a more realistic, force-based brake. Working within a student budget, I explored multiple CAD tools, mechanical layouts and manufacturing approaches before building a functional prototype—and ultimately deciding to move to a commercial pedal set so I could focus on driving and later projects.

- Force-based brake pedal using a 100 kg load cell integrated into the pedal arm

Multiple CAD workflows: Fusion 360 (hobby) and FreeCAD (open-source)

Iterative mechanical design with 3D-printed structural components

Basic FEA to understand stiffness and stress in the pedal arm

Practical lessons in product development, licensing constraints, and buy-vs-build decisions

Context

I was competing seriously in sim drifting and using a Logitech G27 wheel and pedal set. While the wheel was serviceable, the pedals were a significant limitation:

They measured angular position, not braking force.

In drifting and racing, braking is fundamentally a force control task.

At the same time, I was a full-time uni student. High-end load-cell pedal sets and even “budget” steel kits became expensive once I factored in laser cutting, hardware, and shipping.

My goals:

- Build a realistic-feeling brake pedal that responded to force, not travel.

- Match the general pedal effort of my real cars (Camry and Silvia) rather than extreme “200 kg” race pedals.

Use the project as a way to grow my CAD and mechanical design skills, with the option (initially) to one day release a design or kit.

Design & Iterations

Early Research & Concept

Most commercial and DIY pedals I studied used a familiar pattern:

Load cell mounted in the base.

A flat bar or lever redirected force down into the cell.

Heavy steel brackets kept everything stiff and aligned.

It worked, but required a lot of material to route the forces cleanly. I wanted to simplify the load path and reduce the amount of hardware.

My key concept:

Place the load cell inside the pedal arm itself,

Let the arm carry the load directly,

- Use linkage geometry (inspired by a cam-style commercial pedal) to shape how the pedal firms up through its travel.

I selected a 100 kg load cell for the brake for plenty of headroom, with smaller cells planned for clutch and throttle later.

In the first iteration, I kept manufacturability as simple as possible:

- Flat plate components that could be hand-drilled using printed drill guides.

- Simple linkages pushing onto a load cell, mainly to prove the kinematics and geometry.

No attempt yet at a polished kit—this was about learning and validating the idea

CAD & Licensing Detour

Lorem ipsum dolor sit Initially I modelled everything in Fusion 360 using a hobbyist license. That raised an important question: if I ever wanted to sell or share the design commercially, I’d be constrained by the license terms.

To keep that door open, I switched to FreeCAD, which:

Is open-source with no restrictions on commercial use.

Has a different (and less mature) assembly and constraint workflow.

FreeCAD forced me to deeply understand how constraints, references and assemblies worked—especially when small changes would occasionally explode an assembly and require careful repair., consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

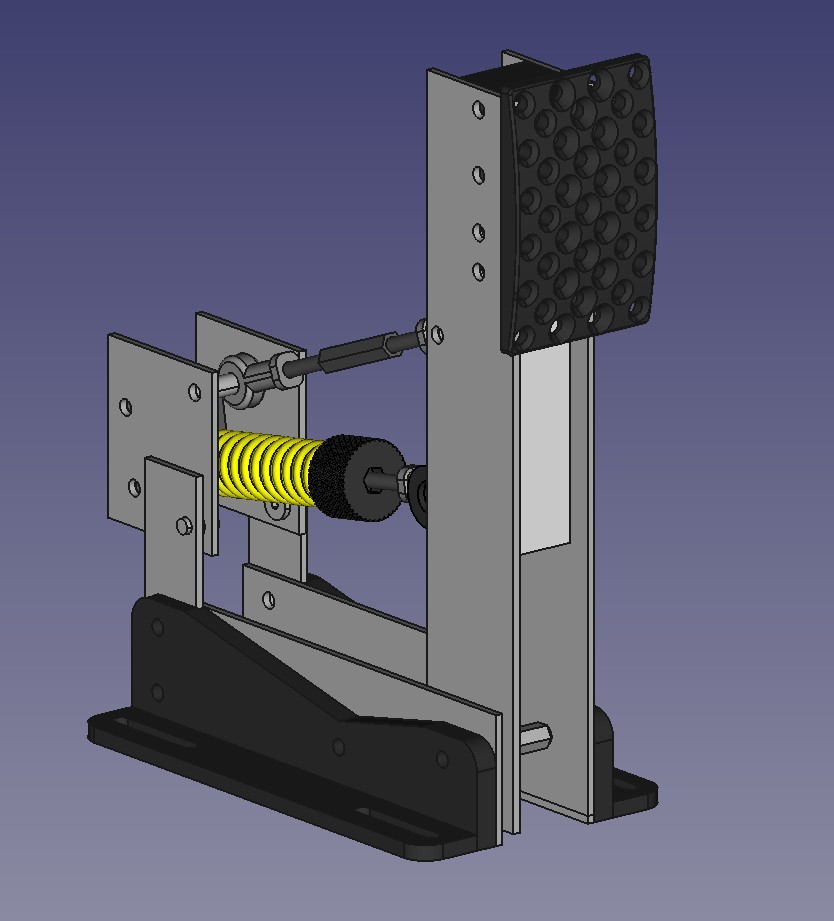

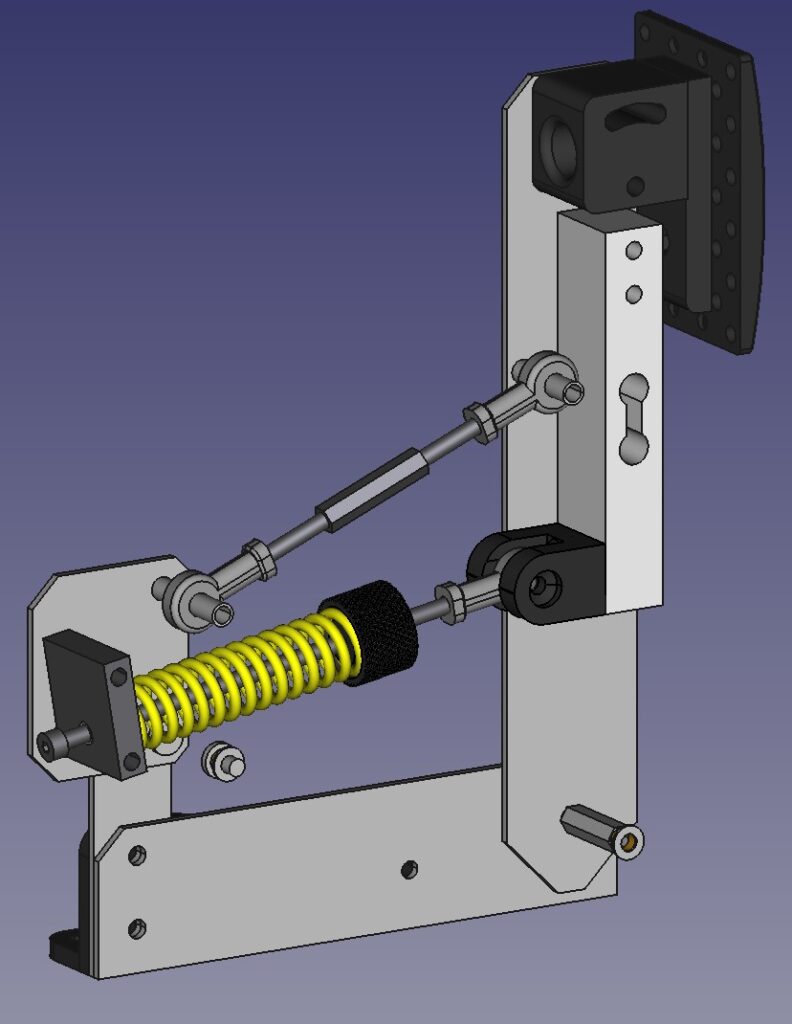

As I iterated, the design evolved into a more advanced brake pedal:

Integrated the 100 kg load cell.

Added adjustable angles and a spring/elastomer stack for tunable feel.

Experimented with linkage geometry inspired by cam-style pedals to create a progressive force curve.

This iteration moved beyond “flat bar pressing on a sensor” and closer to a realistic, tunable brake system.

Returning to Fusion 360

Over time, the fragility of FreeCAD assemblies (constraints breaking on recompute) started to cost me significant time. At that point I made a strategic decision:

- Move back to Fusion 360 for day-to-day modelling.

- Treat the pedal project as a personal R&D exercise, not a product I’d sell.

Prioritise a robust, working design for my own rig.

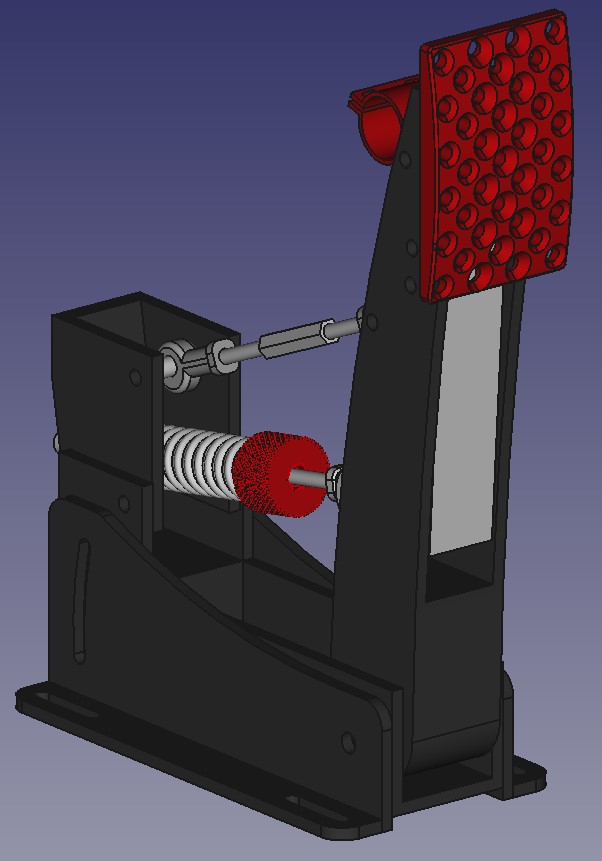

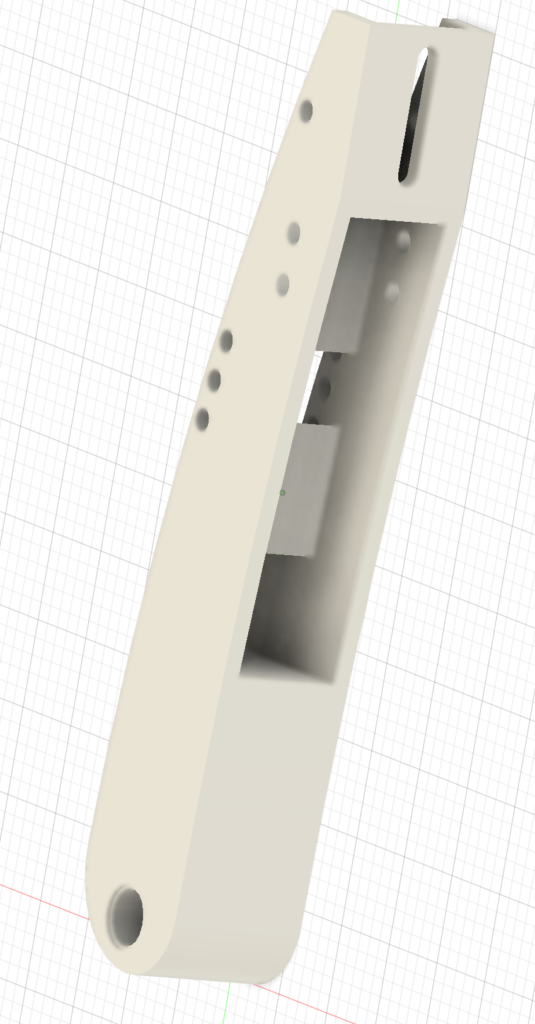

In this “Mk2” phase:

- The load cell sat inside the arm, not in the base.

- The arm was hollow with internal ribs, tuned to carry forces along deliberate load paths.

- The outer form balanced ergonomics, stiffness and printability.

FEA & Structural Refinement

To sanity-check the design, I exported the arm into FreeCAD again and used its FEM tools for basic static analysis.

The FEA runs showed:

- High stresses and deflection concentrated near the top of the arm in earlier, unbraced versions.

How small changes in wall thickness and rib placement affected stiffness and pedal feel.

That fed directly back into the Fusion models, guiding where to:

- Add internal bracing.

- Remove non-critical material.

Balance stiffness with print time and weight.

With the design stabilised, I printed a working prototype:

Used a repaired and tuned 3D printer for structural prints.

Checked dimensions with digital calipers and reworked mounting holes and threads where needed.

Integrated rose joints with internal bearings for smooth articulation and easy alignment.

Temporarily used a spring with the correct dimensions but not the final rate while I dialled in the feel.

The result was a functional, force-based brake prototype: when you pushed the pedal, the linkage loaded the arm, the arm loaded the cell and spring, and the mechanical response closely matched what I was aiming for.

Final / Planned Architecture

Although I never completed the full three-pedal set, the “final” architecture for the brake pedal itself was clear:

Mechanical layout

Load cell integrated into a hollow 3D-printed pedal arm with internal ribs.

Linkage inspired by cam-style pedals to shape the force curve through travel.

Rose-jointed connections for low friction and accurate force transfer.

Spring/elastomer stack to tune the overall pedal stiffness and progression.

Sensing

A 100 kg load cell chosen to provide comfortable, realistic braking forces with ample margin.

Layout designed to keep the load path as direct as possible to minimise unwanted flex and hysteresis.

Manufacturing approach

3D printing for the arm and custom geometry components.

Off-the-shelf hardware (bearings, rose joints, springs, fasteners) wherever possible.

Early concepts allowed for hand-drilled metal parts; later concepts were more aligned with printed parts and potential laser-cut plates.

In parallel, I was already working on a DIY direct-drive wheel. Taken together, these projects formed the beginnings of a complete, self-designed sim racing control system.

Ultimately, when I purchased a second-hand direct-drive wheel that came with high-end hydraulic pedals, I made the decision to stop further development on my own pedal set and use the commercial hardware instead, so I could focus on driving and new engineering projects.

Skills & Takeaways

This project was an important early R&D exercise that built skills I now apply directly in client work:

Mechanical design & CAD

Multi-iteration CAD modelling in both Fusion 360 and FreeCAD.

Designing hollow structural parts with internal ribs and controlled load paths.

Building and maintaining complex assemblies with multiple joints and constraints.

Simulation & validation

Using FEA to identify high-stress regions and excessive deflection.

Translating simulation results into practical geometry changes for stiffness and feel.

Prototyping & manufacturing

Designing parts specifically for 3D printing and simple fabrication.

Integrating standard hardware (springs, bearings, rose joints, sensors) into custom designs.

Iterating on fit, strength and assembly details based on real-world prototypes.

Systems & product thinking

Balancing realism, cost, manufacturability and reliability.

Navigating software licensing and choosing appropriate tools for potential commercial work.

Knowing when to stop building and buy a proven solution to unlock progress elsewhere.

Even though the final rig now uses commercial hydraulic pedals, this project gave me the confidence and practical experience to take an idea from concept, through CAD and simulation, to a working physical prototype—exactly the process I now use when developing and refining components for clients through Omni Mechworks.